- June 29, 2023

- Posted by: Dan Corcoran

- Category: Cybersecurity, Remote Work, Security, SMB, Zero Trust Network Access (ZTNA)

Despite more than a decade of talk, the seminal concept in cybersecurity of zero trust — the assumption that no user or device on a computer network can be trusted — hasn’t been implemented nearly as widely as one might expect from all of the attention.

Despite more than a decade of talk, the seminal concept in cybersecurity of zero trust — the assumption that no user or device on a computer network can be trusted — hasn’t been implemented nearly as widely as one might expect from all of the attention.

The problems include numerous practical and perceptual obstacles, coupled with a complex collection of products that need careful coordination to deliver on its promises. The upshot: Zero trust won’t be a silver bullet for ever-growing cybersecurity woes anytime soon.

The zero-trust label was first developed by John Kindervag when he was an analyst at Forrester Research back in 2010. The way it’s supposed to work is that companies must ensure that every file request, database query or other action on a network comes from a user with the correct privileges. New devices must be registered and validated before they can access each network application, and each user who tries to log in is presumed to be hostile until proven otherwise. Done correctly, it promises to free users from many of the restrictions of more mainstream approaches to cybersecurity, improving defenses.

Since he came up with the idea, Kindervag has gone on to establish a management services provider that offers one of many dozens of solutions that lay claim to his creation. Almost all of the major security providers have a service or product with the term as part of the product name these days, and some, such as Cisco Systems Inc., have made recent product announcements staking the zero-trust territory.

But in practice, despite all these products, a complete zero-trust solution remains largely incomplete — and in some cases unused. John Watts, a Gartner analyst, wrote in the firm’s annual predictions memo from last December that “moving from theory to practice with zero trust is challenging,” and that fewer than 1% of large enterprises are actually using it today.

Moreover, Watts predicted that “over 60% of organizations will embrace zero trust as a starting place for security by 2025 but more than half will fail to realize the benefits.” A report from Nathan Parde of MIT’s Lincoln Lab last May, meantime, estimated the typical zero-trust deployment will take anywhere from three to five years. That is a depressing thought, to be sure.

These results are at odds with other providers’ surveys showing a more rosy picture. Okta Inc.’s State of Zero Trust Security August 2022 report found that nearly all of the 700 organizations surveyed have either already started a zero-trust initiative or have definitive plans to start one in the coming months.

But these results are somewhat misleading. First, years could pass between starting and completing a zero-trust rollout. And second, what someone says and what the organization does are usually two different things, and the survey could have cherry-picked zero-trust fans.

A brief history of cybersecurity

The idea of segregating network infrastructure to provide better protection of various resources arguably began with the first network firewalls and virtual private networks or VPNs that came of age in the mid-1990s. DarkReading has this interesting look way back in 2008 at the many authors who could be called the inventor of the firewall, which most analysts would say was first commercialized by Check Point Software Technologies Ltd., which is still selling it. As to the first VPN protocols, most agree they were created by Microsoft Corp. in 1996, and then became popular at the turn of the century, and are still being sold, by Cisco, Juniper Networks Inc. and others.

What firewalls and VPNs accomplished was to separate networks by enacting various policies: Network traffic coming from internal marketing databases would be allowed in this part of the network, while traffic coming from internal personnel databases would not. Or queries from external networks were allowed to access a corporate web server, but not anything else. How these policies were constructed was the secret sauce of both of these products, and cybersecurity specialists went through lots of training to figure this all out.

That was fine in the era when network perimeters were hard and well-defined. But as web applications were scattered across the online diaspora, the perimeter was no longer a viable conceit, and impossible to enforce. As business used more complex software supply chains, they became dependent on those application programming interfaces and had less insight into how the various software pieces fit together.

This is how many exploits happen, because the bad guys know they can eventually find a way into a network. VPNs and firewalls became new security sinkholes, especially as more untrusted remote devices joined corporate networks.

Enter zero trust

That’s where Kindervag’s zero-trust philosophy came into being. He said that you can’t trust anyone or any app and have to vet every interaction, what some security professionals called “least privilege.” It began an era of adaptive authentication, where people and apps weren’t granted 100% access initially but organizations doled out incremental approvals based on circumstances.

For example, if you query your bank for a current balance, you have to prove you own your account. But if you want to transfer funds, you have to do more, and if you want to transfer funds to a new overseas account, you have to do more still.

Today’s zero trust has created the concept of a “trust broker,” or a mediator or some neutral third-party that will be trusted by both sides of a transaction. Setting these up, especially among both sides that don’t necessarily know or trust each other directly, isn’t easy, especially if different brokers are required for different situations, apps, and types of users.

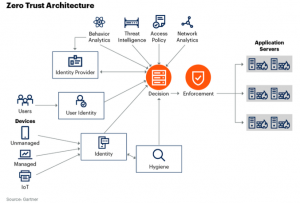

That complexity is where we stand with today’s zero-trust implementations. NetIQ, now part of OpenText Corp., said in its “State of Zero Trust in the Enterprise” report, “Having enterprise systems, applications and data in one location and relying on layers of security tools and controls to keep attackers out is no longer sufficient when the bulk of data and workloads now live outside the traditional network. Zero trust is not a single piece of software but a strategic framework.” One way to visualize this is how Gartner shows its architectural diagram (adjacent) as a series of interconnected parts, such as handling user identity, threat intelligence and applications.

Let’s take a closer look at both “strategic” and “framework” and what they mean for zero-trust implementations. Strategic means that at the heart of any solid cybersecurity plan, as much as possible needs to be zero trust. This is what President Biden’s Executive Order on Improving the Nation’s Cybersecurity was attempting to motivate two years ago, with a goal for federal agencies to implement zero trust security.

Although it was laudable, it is still far from being realized. Even an executive order can’t make zero trust happen by fiat, although recently, federal agencies were told to remove internet accessto a variety of networked devices such as VPNs and routers, something that should have been obvious by now to any information technology manager.

One author said in a post for Security Week last year, “The only way to guarantee zero trust is the proverbial method of unplugging the computer, encasing it in six feet of lead lined concrete, and dropping it into a deep ocean. But this hinders usability.” The trick is therefore to move from this extreme and unworkable position to something that can deliver security and business benefits and actually be useful too. And that is where the framework part comes into consideration.

“There is no right or wrong way to implement a zero trust framework, but it is basically a good construct,” Phil Dunkelberger, chief executive of authentication provider Nok Nok Labs, told SiliconANGLE. “The devil is in the details, and there is no one-size-fits-all users and use cases, making it difficult to deploy.”

His perspective is that IT and security managers are asking the wrong questions when the time comes to formulate a zero-trust implementation plan. “What about zero trust will drive better business outcomes?” he said. “Will we have more secure apps, or prevent data loss, or increase the return on these infrastructure investments?”

Rethinking trust

Perhaps many people have been thinking about zero trust in the wrong light. Trusting a user or an app occupies a continuum, like adaptive authentication: You start out with taking small steps towards total trust, offering a little bit at a time. Moving from an all-or-nothing approach, this “tiny trust” model is better-suited to today’s world.

One way to conceptualize this is to consider adopting microsegmentation to isolate apps, essentially abstracting firewalls to specific workloads and users. Gartner’s Watts says this means “implementing zero trust to improve risk mitigation for the most critical assets first, as this is where the greatest return on risk mitigation will occur.”

Gartner uses five considerations to define zero trust: what the delivery platform is, how to enable remote work securely, how to manage the various trust policies, how to protect data anywhere and what integrations with third-party products are there. That is a lot of touchpoints, for either a framework or a series of any products, to deliver on.

“Zero trust can be applied as a mindset or paradigm, strategy or implementation of specific architectures and technologies,” Watts said in his predictions report. He has several suggestions to help organizations be more successful at its implementation, including defining the proper scope and level of sophistication of zero-trust controls at the beginning of a project, limiting access to devices and applications, and applying continuous risk-based access policies.

“Fundamentally, zero trust means removing the implicit trust (and the proxies for trust) that have formed the foundation of many security programs, with explicit trusts based on identity and context,” he said, “This will require changing the way security programs and control objectives are set, and especially changing the expectations about level of access.”

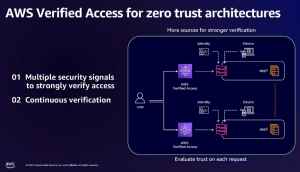

Amazon Web Services Inc. at its recent re:Inforce conference in Anaheim, California, showed examples of how this will work. Jess Szmajda, general manager for AWS’ Network Firewall, showed how existing zero-trust services such as Verified Access and VPC Lattice will work together with a series of new zero-trust services to make AWS more secure. They include Verified Permissions and expanded features to its GuardDuty threat monitoring tool to add better granularity of security policies and more preventative controls. Amazon calls this “ubiquitous authentication.”

The upshot is that organizations should prepare a long and winding road ahead for zero trust. But especially if they can demonstrate the immediate business benefits, it’s worth taking those first steps.

Image: Luigeop/Pixabay

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.